Metaphor. Similes. Analogies. Call them what you will! Are they relevant? Are they accurate?

The petticoat in my analogy is my background. My positionality if you will. As a white, mid-century baby who grew up in South Africa, that petticoat seems to hang out rather often and may even affect my PhD writing! “That petticoat?” “What exactly do you mean by that?”

“Why is she in this school?” asked my year 1 teacher of my mother. Afrikaner children need to go to the Afrikaans school. I could not speak a word of English or Afrikaans for that matter in January 1956. I had just returned to South Africa from Norway where I had lived with my mormor – my grandmother since 1953. I could only speak Norwegian. My dad was a boer so I had a boer surname – van Schoor. That boer surname and my experiences growing up in apartheid South Africa with a father who was racist to the extreme has become the petticoat that I need to watch and tuck back into my skirt or even rip off. Ripping off the racist petticoat happened easily when I arrived in the UK in 2000. But the inequality/discrimination petticoat hangs down below the skirt line every time I think about and compare our UK education system and opportunities children have here in the UK compared with those of most children in South Africa – both black and white.

School experiences of discrimination

Discrimination takes all manner of forms, shapes and sizes. Some may think that discrimination in South Africa was only a white/black experience but it went further than that. Almost all my teachers in primary and secondary school had left the UK in the late 1940s and settled in warm, sunny Durban and their influence was deeply felt in the school system. It was a time when there was a great deal of discrimination towards Afrikaner people. Google tells me that there are 7 different types of discrimination – they forgot to mention surnames.

My surname caused many problems throughout my school years – firstly in primary school and then in high school where I constantly received nothing but E’s and even F’s for English essays. That is, until I wrote the final matriculation examination where I was merely a number and suddenly got an A. I was constantly berated by the Afrikaans teachers about my marks. “ It’s a disgrace that a boer meisie (girl) like you gets marks like this – a B or a C!” In my final year in high school there was a piano competition and I was chosen to perform in front of the school one assembly. After the performance, my geography teacher said to me: “Well, van Schoor, you can at least play the piano well. I am not too sure what else you will ever do with your life, Afrikaaner girl. You should never have been in this school.” My surname italicised to indicate the way she spat it distastefully out of her mouth. Can you imagine the repercussions if a teacher discriminated against a child on the basis of language or surname nowadays? And incidentally, by this stage, I spoke fluent English with as a good a South African accent as any other pupil in the school – all 1000 or more of us.

Now, as a 70-year-old PhD student, I have had to deal with a different type of discrimination from some people. “You’re far too old for this. Go home and knit!” “What on earth are you doing this for. You’re not working now so it’s not going to earn you a penny but cost you thousands of pounds!” Do they understand the reasons for doing a PhD? Clearly “No!”

Growing up in poverty

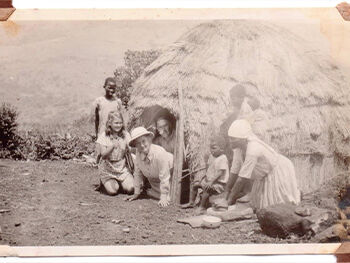

My father died on my 13th birthday. I was not upset. My first thought was – “No more whippings! “- BUT he was the only breadwinner and at the age of 45 had not thought to take out any insurance. My mum had no education. Her education was halted in Norway when the German soldiers used the school building, in Oslo, as barracks. By the end of the war, she was 17 and she and my mormor returned to South Africa where my mormor was a missionary in Zululand. In the photo, my mother is the little blonde girl and my mormor and grand-father (also a Norwegian missionary) were visiting a Zulu parishioner in their hut near the mission station. This was before the war and before they had left for Norway in 1938.

Fortunately, schooling was free in those days and so my education was not affected by the lack of income. However, I was never able to participate in school trips, go to the school dance or go on holidays. I remember wishing I could have a stationery set like other girls in my class with all sorts of coloured pencils, felt tips and pretty erasers. In order to put food on the table, my mum and mormor had a large vegetable plot with every type of vegetable imaginable and with fruit trees like bananas, papaya, passion fruit, lemons, guavas, mangoes and many more. For protein, my mum raised day old chicks so that we had eggs and meat and yes, she decapitated them and then roasted them. We lived in an asbestos and wood frame house in the middle of an acre plot and every time the wind blew I was terrified that the whole place would collapse. Fortunately, it did not but in 2019 in a storm it did collapse.

Fortunately, schooling was free in those days and so my education was not affected by the lack of income. However, I was never able to participate in school trips, go to the school dance or go on holidays. I remember wishing I could have a stationery set like other girls in my class with all sorts of coloured pencils, felt tips and pretty erasers. In order to put food on the table, my mum and mormor had a large vegetable plot with every type of vegetable imaginable and with fruit trees like bananas, papaya, passion fruit, lemons, guavas, mangoes and many more. For protein, my mum raised day old chicks so that we had eggs and meat and yes, she decapitated them and then roasted them. We lived in an asbestos and wood frame house in the middle of an acre plot and every time the wind blew I was terrified that the whole place would collapse. Fortunately, it did not but in 2019 in a storm it did collapse.

By the time my children were at school, school was no longer free and the school fees were exorbitant as they are to this day. School fees applied to every school and I am not writing about independent schools. When my son started off at high school I had no option but to sell my beloved piano in order to raise enough money to buy his school uniforms, rugby kit, cricket kit and so on. Despite being on a reasonably good salary as a teacher, finding enough money to pay school fees, transport fees, buy books and stationery was very difficult. Nothing is free in South Africa – neither then nor now. You may be interested to know that the school fees in a state school presently amount to the equivalent of £1500 to £3000 per year. If you don’t pay, you leave. I only had two children to put through high school. What does an ordinary South African family with three or four children do? A University-trained teacher earns in the region of £11000 - £15000 per annum. When I think about this inequality in education and compare it to the resources available in the average UK school - my petticoat starts creeping down!

What is she on about you may be thinking! My PhD topic concerns shadow education in the Black Country. The title is “Investigating private tutoring in GCSE mathematics and its implications for educational inequality in one geographic area.”

I make no excuses for using the metaphor, if that is what it can be termed – of a petticoat – to describe my positionality in research. Mark Bray of the University of Hong Kong has used the metaphor of a shadow to describe private tutoring (Bray, 1999, 2006, 2007). How accurate can a metaphor be when related to another topic? How accurate is Bray’s shadow metaphor and how has it affected other researchers? I will partly be exploring this in my thesis, but I start here by looking at the physics of a shadow and how this has been overlooked when the comparison was first made. Researchers using the analogy of the shadow state that the shadow mimics mainstream education. To mimic means to resemble closely and private tutoring is very different to classroom education, hence not a mimic. There are also statements that when the school curriculum changes so does the shadow. That has not been true in 2020-21 where the school system almost entirely disappeared and tutoring took place in homes right across the country blurring the boundaries between homeschooling and private tutoring.

So terminology that we use is important as it might not only affect our work but the work and research of many other studies that follow. Almost every paper written about private tutoring quotes the shadow metaphor and yet it has serious flaws.

How does my back story – my petticoat – affect my study? I have had to recalibrate my thinking about poverty and inequality in the Black Country and not compare it to my own poverty-stricken background or to the even more poverty-stricken background of the black people in South Africa. There are still times that the petticoat hangs out and I find the comparison difficult and I find myself thinking: “What inequality? You call that poverty!” But with time, data collection and using the Sen-Bourdieu framework I will be able to make sense of my experiences, my thoughts and my data and synthesise it to create a different theory on inequality, private tutoring and shadow education.

References

- Bray, M. (1999). The shadow education system: Private tutoring and its implications for planners. 2nd ed. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning, UNESCO.

- Bray, M. (2006) “Private Supplementary Tutoring: Comparative Perspectives on Patterns and Implications.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education 36 (4): 515– 30.

- Bray, M. 2007. The Shadow Education System: Private Tutoring and Its Implications for Planners. 2nd ed. Paris: IIEP-UNESCO.