Indian Noblemen

Much of the recruitment, particularly as the war prolonged, took place via noblemen and recruiting officers in India. Wealthy and influential landowners were promised commission and large chunks of land should they help recruit soldiers for the Allies. By the end of the war, a handful of noblemen had amassed large amounts of money and land as a result.

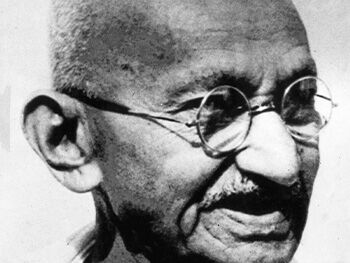

One of the most famous recruiters was Mahatma Gandhi, who played a key part in recruiting thousands of soldiers in the Kheda region of India. Gandhi made a deal with the Viceroy at the time, writing to him in a letter: ‘I will be your recruiting agent for putting together an Indian army for the First World War’.

Since the late nineteenth century, the recruitment process in the Indian army was based on a ‘class system’ stemming from British influence on the region, as well as the ‘martial races’ doctrine. Aspects of Indian society were based on the ‘caste system’, in which there was a societal hierarchy based on ancestry, ethnicity and profession. But in the decades preceding the war, the British military had also recruited from the north and northwest of India, such as the Punjab, due to the belief that its people were more suited for battle. Among the reasons was the rugged terrain of the area, which may have made them more prepared for the physical hardships of war.

By the start of the war, the martial race theory had become an essential part of the recruitment process in India. In the decades before the war, a series of official Recruiting Handbooks, hundreds of pages long,had been written by British officers, which confirmed the importance of the martial race theory to the recruitment of Indian fighters. Handbooks contained sections devoted to each religion and caste, and how they should be dealt with.

Recruitment was organised by recruiting officers, each in charge of a particular class or clan of potential soldiers. Indian recruiting parties also operated in the villages to help build specific regiments. Recruiters had to ensure that potential soldiers were of what was deemed to be a belligerent clan, and even had trick questions at their disposal in case they needed to test the candidate. The most ‘warrior-like’ would be recruited – these would be from low social class and have a darker skin colour; in turn they had a hereditary fighting instinct. The colonial imagination had added a layer of validity and practicality to the already existent racial hierarchy of Indian society. A key result of this recruitment process was that many Muslims would be prioritized to join the British Indian Army. There were many Muslims in the Punjab area, such as the Pathans.

This theory of the martial races continued into World War Two, with Winston Churchill a keen supporter.

Recruitment by ‘Pressgang’ Methods

By 1916, the allies were in desperate need of more Indian soldiers. A new policy meant that Indian units would fight on the secondary theatres of war, leaving the main British army at the Western Front. Small monetary offers began to be made to potential recruits, which increased those who came forward. The rules also became less stringent: usual protocols on height and weight were lowered, and recruiting officers began to venture into new districts that had been previously considered not ‘martial’ enough.

But there was also much forced recruitment, particularly in the Punjab. While conscription wasn’t applied, pressure was applied on Indian officials to fill huge quotas. As a result, recruitment methods began to include kidnapping. Women were even taken hostage until their male family members enlisted to the army.

Much of the unethical recruitment strategies were linked with Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab between 1913 and 1919. O’Dwyer had implemented martial law in the region, placing the military at the head of the state. He attempts to justify such actions in his memoir – India as I Knew It – but there is no denying that his decisions caused huge unrest in the Punjab region, leading to riots, and under his watch, the killing of hundreds of Indian civilians by the military. O’Dwyer, who played a significant role in recruitment for the war, has now become associated with brutality, racism, and as some have called it, ‘terrorist methods’ of recruitment, or ‘imperial terrorism’. In 1940, and back in London, O’Dwyer was assassinated by the Sikh nationalist Udham Singh.