This article summarises research in progress that represents a rehearsal of concept with unconventional methodologies and approaches looking at the work of pastoral practitioners in a sixth form college. Pastoral work is even more important now than ever and as the demands have increased there is a need for professionals to have a comprehensive look at the working practice and environment that staff operate within. How can we look beyond the surface of pastoral practice in a way that allows us to understand and develop practice? I am proposing that methodological innovation is necessary to critically tackle and understand the ‘lived experience’, and ‘troubling’ issues that pastoral practitioners and educators face especially in moments of extremis- such as Covid.

Tuesday 21st February 2021- a selected extract from the autoethnographic writings of a researcher

“The machine delivers consistently and rapidly each time; at the touch of a button, the light turns off but it keeps the coffee warm in the carafe until I’m ready to pour, but this device is only able to function with my intervention having plugged it in, programmed, filled it with both the right amount of water and ground coffee for my particular taste. Feeling in complete control, I receive exactly what I had expected.

I’m sitting at my spot at the bar table, and as I sit back with my hot, tailor-made, freshly brewed Columbian roast looking outside at the same robins that visit. It feels like it’s a weekend, until my 45-minute vibration alert on my phones notifies me of a lesson that I am required to carry out as today is only Tuesday, it is a day I work from home (WFH); a familiar, but a restarted practice that is now looking like it will last for the next few months.Am I working from home or sleeping at work?

Although I can hear family in another room, the sounds are of them clicking buttons, talking through headsets and responding to notifications and phone calls. Logging in, I’m already hit with a multitude of sounds alerting me to new information from several different platforms. I am now swamped with several emails, messages on MS Teams and comments that require a response. This is strange, but no longer unusual. In fact, I’ve been here before. No sooner were we preparing to get back on-site to work in January that the government threw us yet another academic-related U-turn requesting that we work from home at very short notice.

I click the ‘Join’ button to MS Teams knowing what it took to get me here, to the point where I can respond with confidence to what I am doing, my new best friend and colleague is LAP265, I don’t need to refer to the sticker at the top to identify them anymore when I need to troubleshoot with an IT technician. I am exposed to yet more initials on the screen and myself in yet another artificial background.

Like it or not, I have now become one with the machine, this familiar headwear is connected directly to LAP265, I am synchronised with material items that used to be simply tools, to the point where I now wonder which entity is ‘clicking’ who into existence?

Methodology

As a researcher, I looked at combining Hauntological concepts (pasts and returns), Rhythmanalysis, and Autoethnography with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to determine a systematic and reliable way to detect rhythms and themes of interest. Semi-structured interviews with a pastoral practitioner and autoethnographic writings of the researcher (who is involved in the development of pastoral practice) were analysed using IPA.

I wanted to see if I could observe behaviours through a Lefebvrian lens, but to offer further reliability in how rhythms can be detected. Notions of temporality, space, returns and repetitions, rhythms, disruptions and moments that affect professional practices for both myself and pastoral staff, rhythms that are ‘slow’, hidden, unconscious, destroyed and recreated rhythms and how they are linked rather than fragmented were of interest in understanding ‘lived experiences’ (Lefebvre, 2004).

The Results and Rhythms detected by IPA

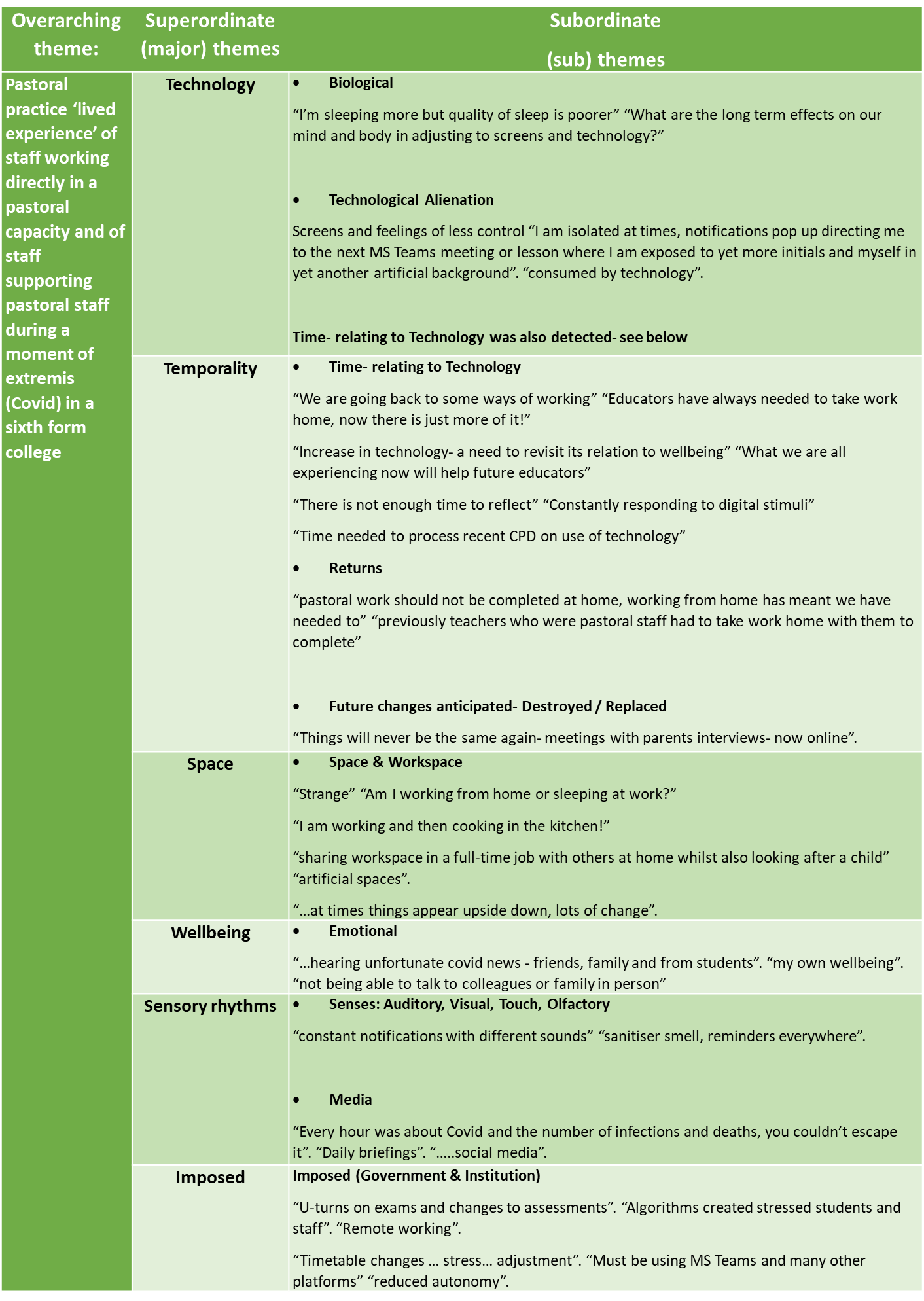

Analysis of the data revealed six master superordinate themes and ten subordinate themes whilst using IPA and these can be seen as interconnecting themes that are rhythmic in terms of how participants described their ‘lived experiences’ (see Figure 1 below). The findings from participants though are not a primary goal of this paper, but it does provide some insight into the outcomes and ability of IPA to detect rhythms in pastoral practice.

The findings in this instance (for now) are less significant to the aims but are reported to show the outcomes and potential analytical techniques of IPA that can be applied to demonstrate rhythmic pastoral practice. This ‘close-to-practice’ approach demonstrates that this innovative combined approach can be used as part of a wider thesis to study several key moments that pastoral staff have needed to work under and is a means to develop pastoral professional practice and respond to training needs in this area.

Find more of Kevin's work via his website and Twitter account.