Shi Jinsong was born in Hubei, China, in 1969. He graduated from the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts with a BFA, specializing in sculpture, in 1994.

Biography

Shi Jinsong pontificates on the contemporary state through his mixed media installations and sculptures that draw on traditional aesthetics. His seminal body of stainless steel work consists of parodies of objects associated with comfort and nurture – baby carriages, a child's rattle – menacingly crafted in razor-sharp blades. Shi maintains a dialogue that juxtaposes globalisation and consumerism with mythic cultures from the past, often diffusing the conversation with a jocular sensibility.

Exhibitions

His recent solo exhibitions include SHI JINSONG - A PERSONAL DESIGN SHOW (Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016); Shi Jinsong’s Art Fair sixth stop: Free Download (Klein Sun Gallery, New York, U.S.A., 2015); Garden of the Owner of the Art Materials Company (Phoenix Art Center Shanghai, Shanghai, China, 2014); and You Won’t Believe It (Galerie du monde, Hong Kong, China, 2014). His recent group exhibitions include Chinese Whis-pers-Uli Sigg Collection Exhibition (Kunst museum Bern, Switzerland, 2016); Ulaanbaatar mandarin short film 2016 (Mongolian National Art Museum, Ulaanbaatar, 2016, China); Collecting the Past To-wards the Present - a Conversation Between Now and Then (BA ART SPACE, Shanghai, China 2016).

His work is in major institutional collections around the world including the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France; Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands; Uli Sigg Collection, M+ Museum, Hong Kong; and the White Rabbit Collection, Sydney, Australia.

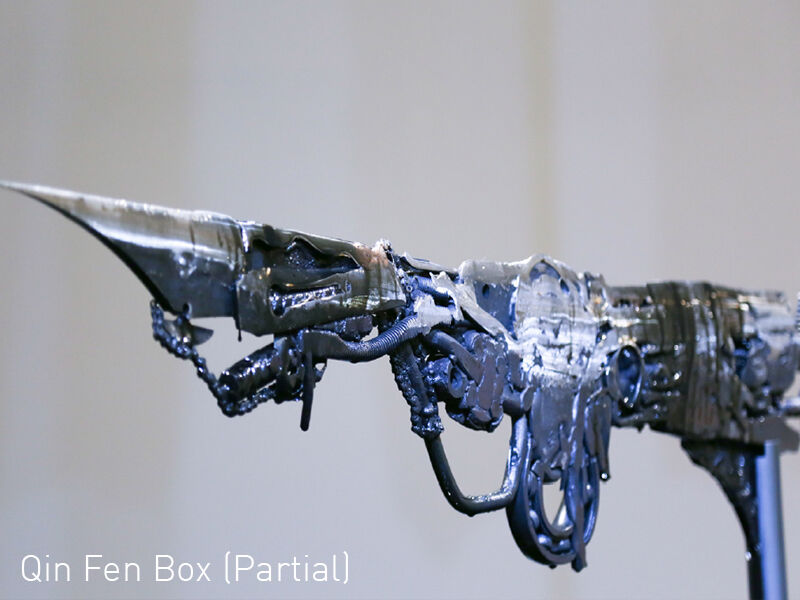

Qin Feng Box

Shi Jinsong’s works have always possessed a certain strength, and even a hidden ferocity. In creating his work Qin Feng Box, Shi benefited from his understanding of traditional Chinese Kunqu opera. In his view, this ancient opera form, which originated in the middle period of the fourteenth century and is based on the Kunshan melody and its folk songs, is a kind of transformation: ‘A carefully studied and refined version of everyday life, thereby turned into a different aesthetic system.’ For this exhibition, Shi collected a variety of daily household items (pans, bowls, knives, forks, spoons, as well as different kinds of tools) as the basis for his production. Through various fusion and combination processes, he produced an array of composite raw materials; then, through pressure, forging, and a long grinding phase, he forcefully transformed these material shapes to grant them a different morphology. The result, strictly speaking, is a blade, but it is devoid of either scabbard or handle; it is a pure, chilling threat. What Shi borrowed is not the concrete form of any actual knife, but rather a vision of the knife presenting a long-extending and finely polished mood, or in other words, the shape of Kunqu opera. As a result, on the one hand, ordinary household utensils are ‘exposed’ as homicidal weapons, turning the ‘everyday’ into the ‘extraordinary’; and on the other hand, the long-sustained endurance at the heart of this production process suddenly becomes the expression of an extreme form of invasiveness — exuding a sense of imminent crisis; the premonition of an oncoming, deadly blow.