University News Last updated 13 November 2019

If you study with us, you'll be supported by our tutors and technicians, many of which are practising artists, designers and researchers. We met Senior Lecturer Stuart Whipps, who told us more about his practice, the benefits of being an artist in Birmingham, and how his work can support you to find your creative vision and place within the city.

Can you tell us a little about your practice?

The easy way I like to talk about my work is that I do things that I don’t understand and don’t know how to do. It’s working outside traditional art and design methods to work with people who have knowledge and expertise about something I don’t understand. I also like the idea of working on something that can be simple, but also very complicated at the same time.

You recently exhibited your work ‘The Kipper and the Corpse’ at IKON Gallery. Could you tell us a little more about that?

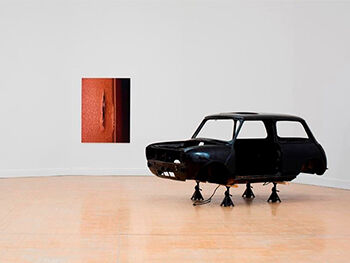

I bought a 1979 Mini that was built at the Longbridge Motor Works in Birmingham. 1979 was the year Margaret Thatcher was elected and also the year Derek Robinson was sacked as the Union Leader at Longbridge. It remains the peak of days lost to industrial action in a year, so I like the idea of this car that comes out of this tumultuous period would somehow carry some of that narrative with it.

Through the restoration process I worked with ex-workers from the factory to completely restore this car. There is something about the very direct material exploration and restoring a car, something I didn’t know anything about. You’re placing your faith in people who do have that expertise and that puts you in a bit of a vulnerable position. You’re having to defer to other people's knowledge and skills, and I think that opens up conversations in a way that is very different to approaching a community about an arts project. It’s on the community’s terms rather than the artist's in that sense.

The car is one part of a very larger body of work that is trying to make sense of the closure of that factory. Lots of my family have worked in the motor industry across the Midlands and I’m exploring what it means for your identity to be shaped by a place or an industry. What does it mean when that place is no longer there?

I spoke to students recently about making work that looks at class or power; it’s far too broad. Even if you think about the making it about the factory, it’s still too big. So I started by saying “I want to make a piece of work about this one vehicle of millions, from this one moment in time as a starting point to think about all of these other things.”

You’re also busy in the Birmingham art scene – could you expand a little more about that and your experience with Grand Union?

I was a founding director of Grand Union, which mainly consisted in hustling to try and get space and submit funding bids to the council before getting our hands dirty in building it. I was one of the people who built it – both literally and metaphorically.

To see it become a resource for our current students and recent graduates as we get them to think about how they use Birmingham as part of their life and practice is great. To be part of bringing this into the city is something I’m really proud of, but I’m also proud of the work the current directors of Grand Union have continued doing, way beyond anything we’d ever imagined when we started.

I’ve also been involved in setting up a graduate residency each year for four graduates from across the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media. The students chosen are given a free studio at Grand Union with mentoring from the directors, artists and practitioners that are based there. It’s just starting its third year and it’s been brilliant for all the participants. We’re really pleased to continue that relationship.

How important is the art scene in Birmingham for yourself and for students?

The art scene in Birmingham is vital for students. It’s as important as having a well-stocked library or well-resourced workshop. The city also is a living, breathing entity that can sustain the interests and energy of our students and graduates and can be a place that nurtures a career and a practice.

We do a good job here in taking students to key places, but also bringing the expertise from those places to our students through live projects and other initiatives. It means students can feel like they can knock on a door and ask questions of a director of institutions who have worked across the world; it’s not intimidating for them. We ease students in at the beginning, so by their final year they’re really comfortable with the directors of institutions in the city.

The city is yours for the time you’re here – you can make a contribution to it as well as gain from it. We are the University for the City.

How do students benefit from being taught by artists such as yourself?

I think it’s important that my practice gives me my authority to teach. It’s about having a consistent engagement with the arts and creative community of primarily Birmingham, but also beyond that.

What we’re able to do is help students position themselves within the external world too, so you’re assisting them to make the links between their practice here in the art school and give them the opportunity to meet people outside the institution and have conversations about their work and to see how it fits into the world outside the school. Practising is essential element to be able to do that.